The UN climate talks at the Cop26 summit in Scotland are in a crunch final week, with countries under pressure to act amid warnings of disastrous global heating. But one source of emissions that is often overlooked is literally in front of us every day: our food.

The steps it takes to bring food to our tables – everything from production to processing to food waste – are responsible for between 21% and 37% of total global greenhouse gas emissions, according to a 2019 report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Cutting emissions from each of these steps will be crucial in limiting the Earth’s warming.

In September, ahead of Cop26, the United Nations held its first food systems conference, though it faced criticisms for a lack of concrete actions and favoring agendas of giant food corporations over small-scale sustainable farming. While there have been some announcements at Cop26 of commitments around sustainable agriculture and less polluting farming policies, the summit has disappointed many advocating for food systems to be more central in the climate debate.

Not every country is equally responsible for the scale of food emissions and, not surprisingly, the top emitting economies largely correlate to how many people live there. In 2015, the US was the third highest food emitter in the world, accounting for 8.2% of the global total, according to a study published in Nature Food.

And in the US, food emissions are actually increasing, reflecting a trend among developed countries.

That’s largely because of the growth of emissions outside the farm – things like packaging, transport, retail, consumption and food waste. By contrast in the developing nations, crop and livestock production, on-farm energy use, and deforestation are the main drivers of emissions, according to new data released by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations.

In addition, this data doesn’t reflect emissions from food the US imports into the country. “The US is a big consumer importer of [food] products from other parts of the world,” says Francesco Tubiello, researcher at the FAO.

Per capita, the United States accounts for 3.8 tonnes or roughly 8,300 pounds of CO2-equivalent food emissions.

So why does our food system account for such a huge portion of global emissions?

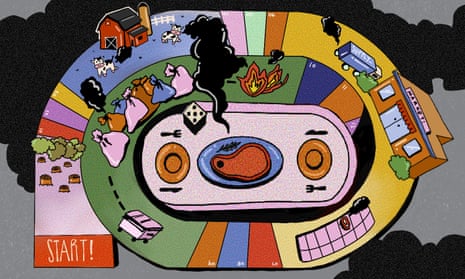

We can best understand this by looking at how our food gets from the ground to our plates – and eventually back to the earth. There are four main areas of food emissions: land use, production, supply chains and waste.

1. Land use

The land where farmers grow crops and raise livestock accounts for a huge portion of food emissions – about 5.7bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent. Of all the habitable land on Earth, half is used for agriculture – and nearly 80% of that land is for livestock.

This means agriculture reduces the forests, grasslands and other land ecosystems that play a crucial role in absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere through photosynthesis. A 2017 study published in Nature found that vegetation holds about 450bn tonnes of carbon.

The major categories of food emissions: land use

Producing beef goes hand in hand with cutting trees for pasture land, trees that once helped remove carbon dioxide. Moreover, grazing an excessive amount of livestock for an extended period, otherwise known as overgrazing, doesn’t allow for sufficient recovery of land vegetation. Overgrazing is the number one cause of land degradation, accounting for 35% of human-induced reduction or loss of healthy soil quality.

Meanwhile, insufficient moisture and nutrients in the soil are making the Earth’s vegetation less able to capture emissions. Some 86% of land ecosystems around the world are getting less efficient at capturing it, according to a 2020 paper published in Science.

2. Production

Atop agricultural land, humans grow an immense amount of food, which includes everything from cultivating crops and raising livestock. And it’s that process that accounts for the highest portion of emissions in the food system: about 7.1bn tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions.

Most of the emissions in this category (57%) come from the production of meat and dairy products. In fact, growing one kilogram of an animal-based product requires up to 50 times more emissions than growing one kilogram of a plant-based product. This is especially a problem because humans, particularly in developed countries, consume a huge amount of meat. For example, the average person in the US consumes 274 pounds of meat a year, not including seafood – about 40% more than 1961, according to the USDA.

The major categories of food emissions: production

Livestock belches methane, as well as releasing it through manure. Over a 20-year period, this potent greenhouse gas has 86 times the warming potential than the same amount of CO2.

At the start of Cop26, Joe Biden delivered a plan to limit global methane emissions by 30% by 2030. Two-thirds of the global economy – including, for the first time, Brazil – have signed on to the pledge. But achieving this target is dependent on all 90 countries living up to their promises, which historically has not been the case.

In addition, growing livestock means farmers also have to grow crops to feed that livestock. Animal feed accounts for 41% of the total grains grown worldwide, while grains for human consumption accounts for 48%.

When it comes to emissions, cattle are by far the biggest culprit – particularly cattle raised for meat, which account for a quarter of all animal emissions. Cattle raised for dairy emit 60% less than animals raised for meat, but given the amount of cow milk humans consume, that still makes it the second-biggest source of animal emissions.

But that doesn’t mean plant-based emissions are negligible.

In order to grow crops – which feed both humans and animals – farmers use fertilizers which emit nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas with roughly 300 times the global warming potential of carbon dioxide. When it comes time to harvest the crops, farmers use heavy machinery such as tractors which run on fossil fuels.

In 2019 the production of rice – a staple crop for billions of people – reached 755mn tons worldwide. One study estimates that for every 1kg (2.2 pounds) of rice, the crop emits 4kg (8.8 pounds) of CO2.

3. Supply chains

Getting food on supermarket shelves requires taking the raw product from farms and transporting, packaging and distributing it – and this process produces more than 3bn tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions.

Next time you’re in a supermarket and you pick up a can of tuna, consider the energy used to can, label and package tuna at a factory. While canned products might not require refrigeration, they need to be shipped via trucks, planes or cargo ships to retail stores across the country.

Food transport accounts for 5% of CO2-equivalent emissions from food. Therefore what you eat is more significant in terms of emissions than eating local. Consuming locally sourced meat and dairy products does less to cut down emissions than consuming plant-based products shipped from far away.

4. Waste

Food that hasn’t been sold or consumed reaches its end of life by rotting in the landfills or burned in flames – both of which create emissions. It can also create wastewater, which needs to be treated. In total, waste accounts for 1.6bn tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions.

The major categories of food emissions: waste

Food waste happens at every stage of the food production and supply chain. Exposure to insects, rodents, molds and bacteria can spoil food at the farm gate stage, while equipment outages such as faulty packaging and refrigeration can result in food loss at the supply chain stage. At the retail level, supermarkets that over-order products, or do not sell certain produce that’s bruised or deemed imperfect, contribute to food waste, as well as people who buy more food than they consume and end up throwing it away.

In the US alone, more than 133bn pounds of food (worth more than $161bn) goes to waste every year. Roughly 40% of all food supply in the US is lost.

How the US might reduce food emissions

The Biden administration has announced a handful of proposals to reduce food emissions, including efforts to reduce food waste and cut methane emissions from the food sector.

At Cop26 in Glasgow, Biden reiterated some of those commitments, saying on 1 November, “over the next several days, the United States will be announcing new initiatives to demonstrate our commitment to providing innovative solutions across multiple sectors from agriculture to oil and gas, to combating deforestation.”

Last Friday, the House passed a $1.2tn infrastructure bill that would allocate $47bn for climate resilience amid more frequent and intense floods, fires and droughts. Still pending a House vote is the administration’s proposed budget for the Build Back Better Act. With $555bn intended for climate action, it includes soil conservation and incentivizing farmers to engage in sustainable agriculture practices.

That said, Biden has been unwilling to touch on some of the biggest sources of food emissions: the meat industry. Cutting down on the production and consumption of meat and dairy products would result in huge reductions of emissions and land use.

Though it accounts for a big portion of global emissions, the food system continues to get overlooked. For example, there is no day dedicated to food emissions at the Cop26, and most nations have yet to make commitments on cutting food emissions. “Emissions from food are the lion’s share of the total emissions,” Tubiello says. He urges world leaders to impose comprehensive actions that are not simply monetary incentives and opportunities to keep emitting using carbon credits.

“Many things that are being proposed are just subsidies to farmers disguised as climate action,” Tubiello says. “In the last 30 years there’s been not a dent in the emissions we’ve put out into the atmosphere, so we really need to be serious about reducing them above anything else.”